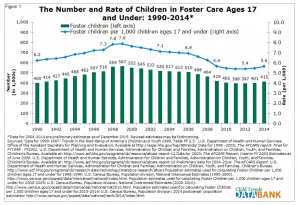

Before 2009, the number of children in Arizona’s foster care system hovered between 6,000 and 9,000.

“That’s unacceptable, but it was consistently normal for us,” said Katie O’Dell, executive director for the Christian foster care and adoption organization Arizona 1.27. “Then, from 2009 to 2010, we started seeing it climbing by the hundreds every month.”

By 2011, there were 10,883 kids in the system. A year later, 13,461. By 2016, there were almost 19,000.

The same thing was happening nationally. The 397,000 children in foster care in 2012 increased to 415,000 in 2014, then to 437,000 in 2016.

“Foster family shortages stretch existing homes thin,” a Massachusetts news outlet reported. In Florida, “Foster kids kept in cars at Wawa parking lot in Hillsborough County.” In Kansas, “Report of Missing Children Latest Concern.”

The headlines pressed urgency onto a growing movement.

In the early 2010s, churches from Colorado to Florida to Arizona to Washington D.C. had begun to band together to recruit and support foster and adoptive families.

The movement would not have been easy to predict. While Christian families had been fostering children for “decades and decades,” the church didn’t have a large or consistent presence in the foster care world, Christian Alliance for Orphans (CAFO) national director of foster care initiatives Jason Weber said.

“We’ve come full circle, from a world in which the church would kind of sit back and sometimes be critical of the state and talk about all the ways they’re falling short to a different approach of humility,” he said. “Churches are saying, ‘Man, we were supposed to be at this party a long time ago. We’re here now. How can we help?’”

“It’s really exciting,” CAFO president Jedd Medefind said. “In a world where there’s so much bad news, this is one place where you really see the church stepping up to be what you hope the church will be.”

That wasn’t dumb luck. Many Christian families and circles had been preparing for decades, long before the first headline. They just didn’t know it.

The Crisis

When the number of foster kids first started to rise, nobody could explain why. Before fiscal year 2012, the number of kids in foster care had dropped for 13 straight years.

“We are concerned about any increases in the foster care numbers, and we are working hard with our state partners to better understand the reasons behind the increase,” Rafael Lopez, commissioner of the Health and Human Services Department’s Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, said in 2015.

Two years later, the department had a better answer: the opioid crisis. Of the 15 reasons states could indicate for why children were removed from their homes, a full third were parental drug abuse (34 percent).

O’Dell also points to the Great Recession, which depressed the income of both families and also states. From December 2007 to February 2010, Arizona lost 11 percent of its jobs—more than any other state except Nevada.

“It’s almost always a tangle of threads—financial poverty, often substance abuse, a lack of resources and education, unemployment, maybe also sexual abuse, a lot of very broken relationships”—that land children in foster care, Medefind said. Most of those factors are exacerbated when the economy goes south.

In Arizona, the rising numbers of children were compounded by a 12 percent drop in the number of foster families.

That wasn’t unusual—at least half of states were seeing fewer families willing to foster. Some of that was due to frustrations with the system—in Arizona, foster parents were getting less attention from overworked caseworkers and fewer resources. The annual emergency clothing allowance was dropped from $300 per child to $150; the books and education annual allowance fell from $165 to $82.50; the camp and vacation allowance was suspended.

Before fiscal year 2012, the number of kids in foster care had dropped for 13 straight years.

There are other reasons to quit: Some foster parents adopt and stop fostering; others drop out because it’s hard to love a child and then let him go. Some experts point to the increase of single parents or two working parents, which leaves little margin for another child.

In Arizona, the Department of Child Safety staff grew desperate, placing kids in foster homes hours away from their community, filling up group homes, and making temporary beds for kids in their offices.

“We hit an all-time crisis,” O’Dell said. “It felt insurmountable.”

The Arizona Republic ran an exposé on the state’s Department of Child Safety, and Redemption Church pastor Tyler Johnson read it. Worried, he met with the pastors of Hillsong Phoenix and Mission Community Church.

“We said, ‘What would it look like if we did something?’” he recalled.

International Adoptions

It wasn’t as if Christian families had never been involved in foster care. Here and there a family would open their home to children who needed care. But they had to be pretty persistent to do so.

“One of the biggest gaps of church engagement in foster care is a huge knowledge and language barrier,” Weber said. Learning the government’s process can be frustratingly confusing.

Compounding that “was the lack of response from the government,” said Shelly Radic, president of the Christian foster care and adoption organization Project 1.27. It wasn’t always easy to get a phone call returned or a question answered.

“And then, if they did connect and go to the [adoption/foster care] training, they felt like they were asked to check their faith at the door,” she said.

Aside from an occasional meal, the church wasn’t generally there for support either. But that wasn’t because the church didn’t care about children.

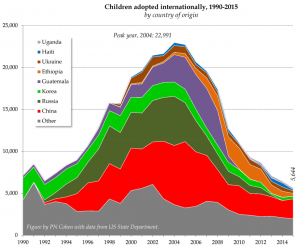

“In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was a real rise in the number of Christian families that were adopting, and a lot of that was international,” Medefind said. “There were a lot of reasons for that.”

One was the internet, which was enormously effective at spreading awareness. Another was the global AIDS crisis—“it created a whole generation of children that needed parents.” (In fact, you can track global disasters through the countries that send the most children to be adopted into American families.)

Over the span of a decade, international adoption rose from around 7,000 a year (1990) to nearly 19,000 (2000), peaking at almost 23,000 in 2004.

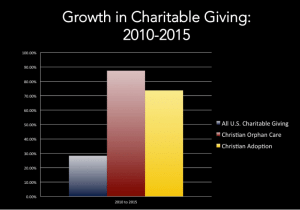

CAFO was founded that year, providing both a meeting place and leadership for those interested in adoption and foster care. “Unified efforts like that bring far greater impact than when organizations work in isolation or competition,” the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability (ECFA) observed.

ECFA backed that up with numbers: Giving to Christian orphan care rose more than 87 percent, and giving to adoption rose by more than 73 percent from 2010 to 2015, much higher than the overall increase of about 28 percent.

The coordinated rise in international adoptions “opened the entire church to the idea that there are children who need families, and that God invites his people to be homes of welcome for them,” Medefind said. “People began to pay more attention to the way in which Scripture calls us to care for orphans—of how it speaks to our own adoption into the family of God. It began to be a part of church culture.”

Then, starting in 2005, international adoptions began to plummet. Reasons range from stricter State Department regulations to the relaxing of the one-child policy in China to countries closing international adoptions until they can clean corruption from their systems.

But many churches and families had become passionate about caring for children in need.

“Anytime you limit the opportunity for the expression of that desire, you’re going to see it more somewhere else,” Medefind said. “People are tempted to pit [international adoptions] against [domestic adoptions and foster care], but really, inter-country adoption may be the primary catalyst for the new awareness of needs in foster care.”

Project 1.27

In 2012 in Arizona, the three pastors met to discuss the foster care crisis. There were so few organizations helping churches foster and adopt domestically that all three thought of the same one.

Project 1.27 (named for James 1:27) had launched about five years earlier, when a pastor in Colorado began wondering why the 875 adoptable children in his state were still waiting for a family when there were 1,500 churches sitting in the Denver metro area.

Project 1.27 staff built relationships with state personnel and advocated for consistent parental training from county to county. They visited churches, explaining the need, teaching leaders how to build adoption ministries, connecting families in support groups, and offering their training course as often as they could.

Last month, Project 1.27 celebrated its 400th adoption. In seven years, the number of children waiting for permanent homes in Colorado plummeted from 875 to less than 300.

Last month, Project 1.27 celebrated its 400th adoption. In seven years, the number of children waiting for permanent homes in Colorado plummeted from 875 to less than 300.

But along the way, Project 1.27 realized something.

“We found our churches had been talking about family reunification and foster care as if it were the dark side of adoption,” Radic said. “Emotionally, it’s way easier to say we need to rescue children who don’t have a family. We become the heroes. It’s hard to go from there to saying, ‘We need to step into the messiness—often generational messiness—of these families and show Christ’s love.’”

Project 1.27 made that shift around 2012—just as the foster care crisis was hitting the country. For Radic, it’s a sign of the maturing of the Christian adoption movement.

“Maturing often happens when we step into things,” she said. “Our instinct is to help and serve, but we don’t know how. We learn as we go.”

From Adoption to Foster Care

In 2012, Arizona 1.27 was launched as a bridge between the state and the church. It offered state-approved training for families as well as training for a wrap-around team from the church to support the family. It asks for all-in buy-in from churches—“this isn’t a bulletin announcement or a table in the lobby,” O’Dell said. “This is a discipleship of people’s hearts and minds.”

Arizona 1.27 leaders knew, going in, that foster care and adoption wasn’t going to be a quick win. But they had no idea how slow and hard it would be.

“Many people feel supported, and more don’t,” Johnson said. “[The church] opens itself up to, ‘You said you were going to do this, and you’re not.’ Your children’s ministry has to change, because there are now kids with substantial trauma in your ministry. You need way more counseling, because now marriages have tensions on them they wouldn’t have otherwise.”

In sum: “There are a lot of reasons why churches wouldn’t do it,” he said.

But a lot of churches did. Since 2010, close to 2,000 families from more than 90 churches have started the process of fostering or adopting with Arizona 1.27. Through 2017, those families adopted 450 children and fostered more than 2,150.

Arizona 1.27 is now the biggest recruiter of adoptive and foster families in Arizona.

Change in the Church

“Adoption and foster care have created an environment for discipleship unlike anything we knew we were getting into,” Johnson said.

That’s because fostering a child can break your heart.

“It’s really tempting to just do minimal care and not let yourself become attached because it seems like it would be less painful when they leave,” said Becca, a single woman who fostered two boys in Austin, Texas. “I look at Scripture and see that’s not how Jesus has loved us. I am called to lay down my life for these guys, no matter how long they’re in my home.” (Watch a video of Becca’s story at the end of this article.)

Intellectually, “it’s easy to see healthy family reunification is the best outcome whenever it’s possible,” Medefind said. “Emotionally, it can leave a hole in your heart. But embracing a child for life, with all of her trauma and beauty, joy and fear, is costly too. No matter what, you’ll share in the pain these kids have known.”

“Our lives have taken on the shape of Jesus’s life—this dying and being resurrected,” Johnson said. “And you don’t find resurrection until you’re dying in sacrificial love on behalf of somebody else.”

In championing adoption and foster care, Redemption is asking members to do something that’s too hard for them to do.

“Now they’re following Jesus for survival,” Johnson said. He points to the bookstore that Redemption just converted into a prayer room.

“I don’t think we would have been pursuing prayer the way we are if foster care and adoption hadn’t pressed us to feel this level of need,” he said. Improving discipleship this way “wasn’t the plan—the plan was to be obedient. I don’t think I understood the whole of it—how it could begin to affect the church.

“One of the most terrifying parts of the whole thing is that we’re going to have some seriously hard stuff coming down the pike,” he said. “The people who adopted a 5-year-old are going to eventually have a 19-year-old.”

That’s another sign of the movement’s maturation, Radic said. People are realizing that “adoption is not a miracle cure. Children have experienced huge amounts of trauma that is impacting their brain and behavior. Those families will need support and encouragement forever.”

“Theologically, it feels very much like you’re preparing people to suffer, which is what the Bible is doing all the time,” Johnson said. “I don’t think the gospel answer is, ‘Clench your teeth and do it.’ We need an inner life with God. We really need that.”

Johnson encourages his church by reminding them that we are orphans that have been adopted by God.

“That idea is huge,” he said. “But the other part that we’ve begun to press into is Ephesians 5:1—‘Be imitators of God.’ How do you mimic a God who is unseen? In essence, you mimic Jesus. Well, the shape of Jesus’s life is Philippians 2—a downward descent on behalf of others.”

It’s definitely not the health-and-wealth gospel, he said. “It’s pretty much the opposite.”

Spreading the Movement

Arizona wasn’t the only state with a foster care crisis. Arizona 1.27 was followed quickly by DC 1.27 and One Hope 27 in Wisconsin. (Now the 1.27 network has eight ministries, with four more in the works.)

In Florida, 4KIDS was launched out of Calvary Chapel Fort Lauderdale; in 2016, it placed 546 children in Christian foster homes. The CALL has recruited more than half of all foster families in Arkansas. Those Christian families have cared for more than 10,000 children and adopted more than 800.

Since 2013, Promise686 in Georgia helped parents adopt more than 315 children, recruited 163 new foster homes, and taught 2,500 volunteers how to serve foster families. In 2016 alone, the 111 Project signed up more than 1,000 foster families in Oklahoma.

Orphan Care Alliance is training and supporting foster and adoptive families—and their support teams—in Kentucky and southern Indiana, while Safe Families for Children has built an international pre-foster-care support system from Chicago. And Focus on the Family launched an Adoption and Foster Care Initiative and also Wait No More events to recruit families and support the local organizations.

“The sleeping bride has awakened,” Focus on the Family’s director for foster care and adoption Sharen Ford said. “Every Bible I’ve ever picked up says to take care of the fatherless, because God is a father to the fatherless. He uses his church—his bride—to step into that and be his hands and his feet.”

More Than Enough

In a country where 437,000 kids are in foster care, the improvement Christian “bridge organizations” have made can look small. But that’s the wrong way to look at it, Weber said.

“In my county, we have more than 60 kids available for adoption,” he said. “I live in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, where we have many times that many megachurches. We’re not talking about a giant, insurmountable problem. We’re talking about something that can be solved.”

His goal is to get 10 percent of churches in every county in the country involved in foster care or adoption by 2025.

“If we can get to that number,” he said, “then we’d have more than enough.” Every foster child that came into the system would have not just a home, but waiting families from which to choose.

“To get there will take a movement of God through his church,” Weber said.

But he’s optimistic, because he’s watching it happen. “The movement is snowballing. . . . It very much feels like sitting in the stands at this amazing time and watching God do cool things.”

Medefind feels the same way.

“Looking at history, I believe God often uses very tangible factors to spur his people to action,” he said. “I sense that God has been moving his people in remarkably similar ways—across the United States and beyond—to make our ancient commitment of service to orphans again a defining feature of the church.”

Related:

Wanted: Parents Willing to Get Too Attached (Brittany Lind)

Foster Children Need the Church (Brittany Lind)

Becca’s Story:

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.